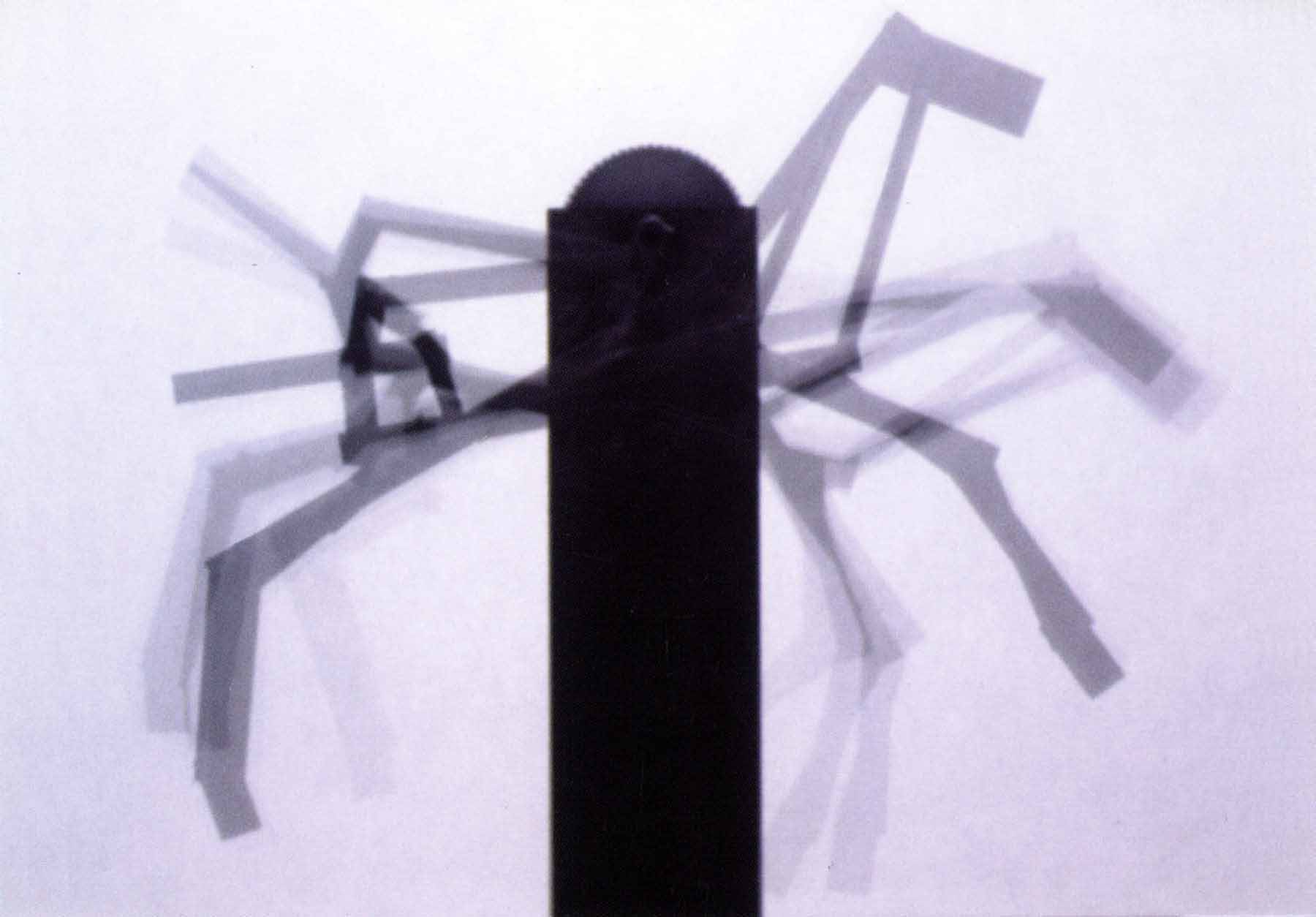

Cadenas Cinéticas Articuladas

Luis Cortés

04/05/00. (Sala 194)

This is the title of an exhibition composed of more than twelve steel sculptures. Equipped with a motor (220 V or 12 V) connected to the mains directly or through a transformer, they reproduce shapes, movements and rhythms of different beings: animals, plants, a mountain, a wave, or other natural phenomena. They are motorized sculptures.

Each of the pieces is composed of a number of articulated elements (from 9 in the “wave” to more than 30 in “Añón’s horse”), according to which they exist in a state of interdependence and none of them is able to move alone or with its own nature. The power of the engine, at a different number of revolutions in each case, passes to a main crank, distributing it to connecting rods and rocker arms. They are what is called in mechanics articulated kinetic chains. Arranged all axes in a single spatial plane, they are mainly silhouettes.

Movement and form are delimited in space. The mechanical functions or mobility of beings, either internally or externally, give them a certain form and this in turn is capable of generating certain movements. The tail of the dolphin, the claw of the leopard, the branches of a tree are forms traced by a mechanical work. In other words, in all beings there is a design of movement.

Synthesized the elements that compose the pieces in straight lines, the only curves that are described are those traced by the mechanisms through turning points, but only in a determined time: they are mainly representations of movement.

I have only wanted to imagine alternatives for art, always betting on any form of technique, which could bring new images, offering different meanings of the world of our being.

I have only wanted to imagine a dolphin’s tail, metallic, coming out of the water, generating effects: a public fountain. A tree confused among real trees, moving with the air. The movement of a wave, perhaps also in case we need to remember them someday.

Luis Cortés

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zUvB6T3-UWk&list=LL&index=27

Some reflections about movement and abstraction in art, motivated by the work of Luís Cortés.

In a certain film by Antonioni, his characters, on a night walk along the port, stop as if attracted by something: moved by the languid and monotonous undulation of the water, a row of chained metallic cylinders swaying and clashing with the fateful obstinacy of a perpetual movement. The characters, absorbed, remain motionless, their gaze trapped by this trivial and fascinating event. A long and attentive gaze like the one we repeat, always, identically, in front of the fire.

Delight and amazement: the slow collapse of the glacier wall; the serene passage of the clouds, crisply uniform; the waters of the waterfall that, with spectacular disorder, rush irremediably into the void. Delight and amazement: Not before the strange, but before something that is inexplicably familiar to us: we look as if remembering.

The millenary experience of inhabiting the planet has made each discovery a reencounter, a stimulus that awakens a forgotten experience. And it is not only the matter that we remember but, fundamentally, its behaviors: the way in which the water flows from the fountain, the way in which the frost breaks under our feet. Phenomena, events, small catastrophes that have imprinted in our brain the respective reflexes, our own motor consciousness, our gestural instinct. It is, in the end, that dark complicity of the eye with the hand that includes us in the gigantic machinery of the world as witnesses and actors.

Luis Cortés proposes a sort of incomplete catalog of movements, all of them attributable to real phenomena, openly declared, baptized with the name of the facts that each piece imitates. Reality is expressly represented and, therefore, summoned; but this is not a case of illusionism. That wise oriental saying that “he who sees the strings of the puppets deserves to be blind” does not hold true here. In our case, the opposite is true: nothing has been understood by those who, in honor of realism, forget or try not to see the mechanisms of these objects.

On purpose and without concessions, the artist leaves us alone with his levers and cranks,

In front of the materiality of the naked and elementary machinery. The motor principle is shown shamelessly, but neatly. For those who know how to see. Or to teach how to look. To make the movement be seen, plainly, crossing the image of the animated object that the piece recalls.

A movement that belongs at the same time to two worlds: to the world of the machine and to the world of the represented object. To the one that is seen and to the one that is not there. A movement snatched from its original owners, metaphorical like that of the robot. Like the slow-motion leap of that leopard, which fascinates us with a sensuality of unseen origin.

A movement that belongs at the same time to two worlds: to the world of the machine and to the world of the represented object. To the one that is seen and to the one that is not there. A movement snatched from its original owners, metaphorical like that of the robot. Like the slow-motion leap of that leopard, which fascinates us with a sensuality of unknown origin and which also alludes to other movements, perhaps other jumps, something we no longer remember. Or like the dance itself, which pleases us because it perfectly imitates something else without ceasing to be pure dance. Pure dance.

To see, then, the machine, to abstract its movement, then to recognize in it the real being and to forget it again to return to the mechanism. The artistic experience is an itinerary of diverse ecstasies: more than an arrival, a journey.

For, in its pure form, figurative art is the fruit of abstraction and, in its appreciation, refers to it; the abstract, stricto sensu, resides only in the concrete; for it lacks autonomous existence outside of thought. The notion of “abstract art” is, in this sense, redundant, and its exercise, practically superfluous.

And so it is that we suddenly discover that the magical movement of Luis Cortés’ mechanical mountain renders irrelevant that random, meaningless oscillation of Calder’s mobiles.

Art does not take shape in the figure or in the formal principle but in the pendulum that swings from one to the other: an oscillation between matter and meaning that does not stop and that keeps us in suspense. And the artistic experience is nothing more than the restlessness that this hesitation arouses.

Norberto Chaves